Today it seems almost unbelievable that it took until 1984 before a women’s marathon was included in the Olympic programme, but from the first modern Games in 1896 until then, only men were allowed to compete at the classic distance. That’s not to say that during these wilderness years there weren’t many women racing in other marathons. The first official women’s world record was set at three hours and forty minutes in 1926, and it was gradually lowered to two hours and twenty-four minutes shortly before the 1984 Games. Despite this it took almost a century before the powers that be finally relented and allowed women to compete in an Olympic marathon.

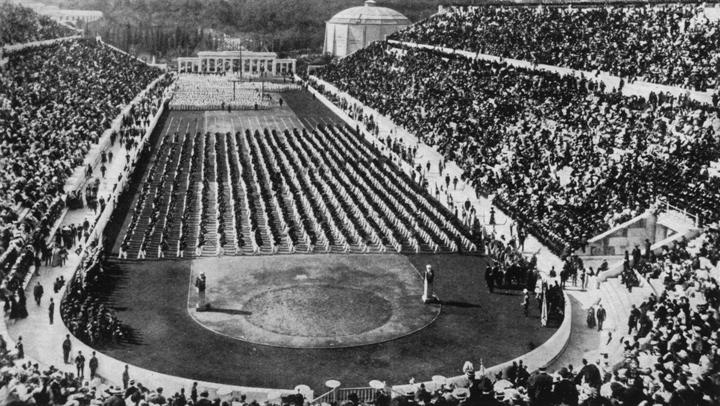

Yet things could have been so different. For on the eve of the very first modern Olympic marathon in Greece in 1896, a woman was amongst the athletes gathered at the Trophy of Miltiades Inn in the village of Marathon making preparations for the race the next day. Had she run she would have set a precedent that might have changed the course of Olympic history.

Stamarta Revithi is a shadowy figure. She emerged from impoverished obscurity to international fame overnight, and then, almost as suddenly, vanished back into anonymity. A thin, intelligent woman of 30, she had lived a tough life and looked much older than her years. After her eldest child died she set out for Athens on foot, looking for work to support her remaining toddler. Along the way she met a kindly runner, who gave her money and, seeing how tough she was, carrying her child and belongings along the dusty road, suggested she tried her luck in the Olympic marathon as a way of attracting an offer of work.

Revithi took him at his word. On arrival in Athens she went to the organising committee and requested the right to run. They rebuffed her, saying the deadline for entries had passed, but this was not a woman who gave up easily. She decided to run unofficially, telling journalists ‘I will compete. If the committee does not allow me to run with the other runners, I will follow behind’ and set of for the start line in the village of Marathon.

The marathon woman attracted a great deal of attention. The local mayor offered her hospitality and journalists flocked to report her story. At a time when women were considered physically fragile and expected to be subservient to men her quick wit, confidence and strong personality made her a fascinating character.

Sadly, Revithi was not allowed to run with the men, but set off alone the next day. Dressed in a long skirt and with long sleeves and wooden soled sandals, she covered the course in five hours and thirty minutes – not bad considering her lack of training, inappropriate attire and the rough roads. She was far slower than the winner of the men’s race, but in finishing she achieved more than at least 8 of the 24 male competitors did. Explaining her slower than predicted time to reporters afterwards she said she would have been faster, but had spent a couple of hours browsing in the shops she passed along the way!

What happened next? Did Revithi manage to get a job as a result of this display of endurance and toughness? Alas, shortly after the race the historical record of Stamarta Revithi falls silent. But whatever the future held for her, she left an indelible mark on marathon history, and blazed a trail for the millions of marathon women that have followed in her determined footsteps ever since.