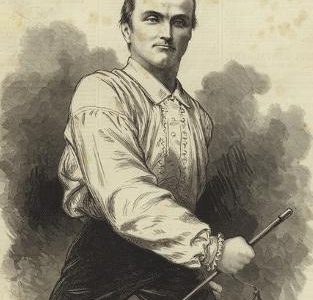

Sprint superstars like Usain Bolt and Dafne Schippers, with their legions of fans and swollen bank balances, seem like a thoroughly modern phenomenon – a product of mass media exposure and the commercialisation of sport. But surprisingly, this isn’t the case. Research by cultural historian Peter Swain has unearthed the fascinating story of one of England’s first celebrity sprinters, who plied his trade almost two hundred years ago.

Born in a small village near Bolton in 1806, Benjamin Bradley Hart started his working life as a weaver. He supplemented his meagre pay by participating in wager races at local fairs and, after proving unbeatable at this level, decided to try his luck against the professionals.

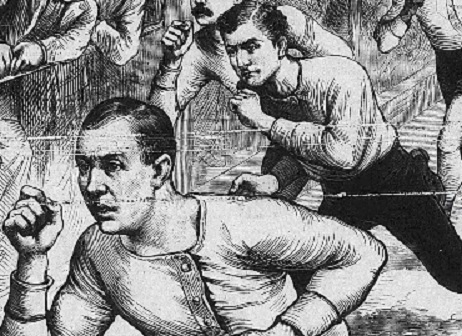

At the time wager races were big business. Runners would challenge one another for an agreed stake, and the public would turn out in droves to watch and place bets of their own. Races were often officiated and promoted by a local publican, who would also act as the ‘stakeholder’, looking after the two runners’ stakes and handing them over to the winner.

Ben Hart’s decision to go professional paid off immediately. He won his first three races – all sprints – for a total of £25. This was a huge sum at a time when as a weaver he was probably only earning about £14 per year. But this was only the beginning. A string of victories meant higher and higher stakes against ever more illustrious opponents. Within a few years he was winning £100 or more for a single race.

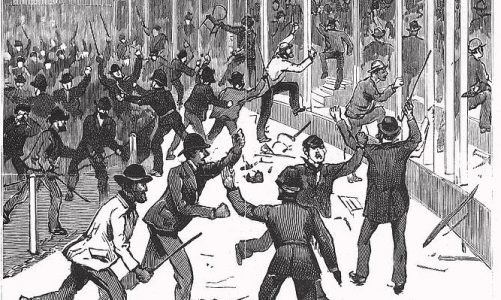

A career highlight came in 1834 when he took on ‘The Mountain Stag’, Thomas Lang, on Kersal Moor. Perhaps 5,000 people watched and punters bet over a million pounds in today’s money on the outcome. After the race carrier pigeons and horsemen spread far and wide with the result: Another win for Hart, naturally.

By now Hart was acclaimed ‘Champion of all England’, ‘Ben the Conqueror’, and ‘the best runner from 100 yards to quarter mile in the British Empire’. His reputation was terrifying, to the extent that rival professionals would issue challenges to anyone in England, ‘barring Ben Hart’. To get races he offered opponents head starts – but almost always won anyway.

Hart’s celebrity was enhanced by his reputation for being one of the good guys. In a sport where cheating and bribery were endemic, he was believe incorruptible. This reputation would serve him well in later life.

As he neared 40, Hart began to meet with the occasional reverse to younger men. He decided it was time to retire. The fortune he had made enabled him to buy a string of pubs, from which he spent the rest of his life as an important and trusted race organiser and coach. He was known as a fair and trustworthy officiator, to the extent that he was even made stakeholder in races involving a runner he himself had trained – like letting a football manager referee a game his team was playing in.

But the move into administration hadn’t dampened Hart’s competitive instincts. A few years after he retired (and having put on a lot of weight) Hart was taunted by a young man who claimed he could easily defeat the old has-been. Like a boxer coming out of retirement for one last fight, Hart couldn’t resist the challenge. He offered to race over 120 yards there and then. Hundreds flocked to watch as the rotund, middle-aged publican rolled back the years to win the race at a canter, and claim one last moment of athletic glory in his long and illustrious career.