Hooliganism is not something we associate with running today. The crowds at track meets and road races are some of the friendliest and best natured of any sport. Yet at the dawn of the era of modern athletics running had a serious problem with crowd violence. In fact, the emergence of the modern sport was driven in part by the desire to rid running of the unsavoury elements it seemed to attract.

One of the most vivid examples of the violence connected with running in the nineteenth century is the riot at Lillie Bridge, in 1887. Lillie Bridge was the headquarters of the Amateur Athletics Club (forerunner of today’s Amateur Athletics Association), and the venue for the national championships. With a capacity of over 12,000 set around a third of a mile cinder track, it was state of the art when it was built in 1866.

Battle of the Bridges

At the end of the 1870s the pre-eminence of both Lillie Bridge and the Amateur Athletics Club was under threat from the powerful London Athletics Club, which opened its own stadium close by at Stamford Bridge. In a bid to take control of the sport the London AC also inaugurated a rival national championship hosted at the new track. The result was that two competing national championships took place in 1879.

In order to ensure its survival in this competitive environment the Amateur Athletics Club needed to maximise the income it received from Lillie Bridge. So the track was rented out to organisers of professional running events, which attracted large crowds and meant high gate receipts, but also brought the gambling and rowdy working-class crowds that many of the privileged founders of amateur athletics wanted to exclude.

The burning of the Bridge

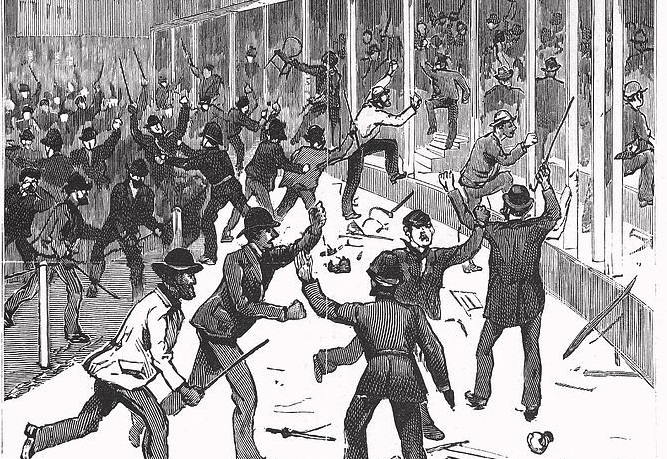

In 1887 a professional race between Harry Gent and Harry Hutchens attracted large crowds to Lillie Bridge, and big stakes were bet on both runners. Things started to unravel shortly before the start when a rumour swept through the stadium that the race had been fixed. One of the runners was not fit, and it seemed gangsters had pressed for the contest to go ahead anyway so that they could make a killing betting against him. The bookies called for the race to be cancelled, and angry spectators demanded their ticket money back. And when the managers of Lillie Bridge failed to provide refunds, the crowd erupted into violence.

The rampaging mob pulled down the wooden structure of the stadium and surrounding buildings, smashed seating and set the wreckage ablaze. The police that were present were beaten up after trying to resist them, and one man died in the chaos. Further police arrived on the scene and eventually managed to restore order, but not before Lillie Bridge was put beyond repair. The venue was closed the following year, never to host a running event again.

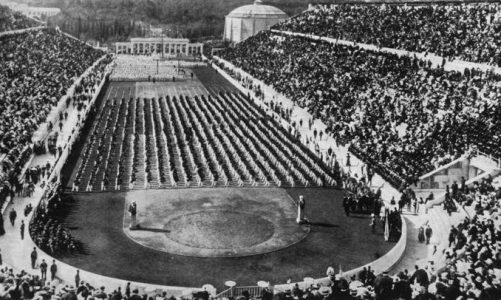

The destruction of Lillie Bridge seemed to confirm the belief already held by many, that professional running was corrupted by criminality and cheating, and that only by adhering to principles of strict amateurism could spectators’ confidence be restored. In the decades that followed the administrators of amateur athletics worked tirelessly to marginalise professionalism, ensuring that prestigious events like the national championships and the Olympics were open to amateurs only. With money out of the equation there was little incentive for athletes to throw races or for criminals to get involved. As a result, amateur running quickly achieved a reputation for honesty and gentility that helped it become the definitive form of the sport for much of the following century.