What’s the most common question you’re asked after finishing a race? In my experience it’s almost always ‘what was your time?’, and talking to other runners it seems this experience is pretty much universal. It doesn’t matter whether you’re an elite athlete or a first time 5k runner, the vital fact is how long it took.

For many of us this focus on times is what makes running so attractive. It enables you to compete with people you have never raced or even met, and by comparing your times to your own past performances you can track your progress in a striking way. But of course, running predates stopwatches, and history shows that this obsession with timing isn’t as inevitable as we might think.

Rise of the clock watchers

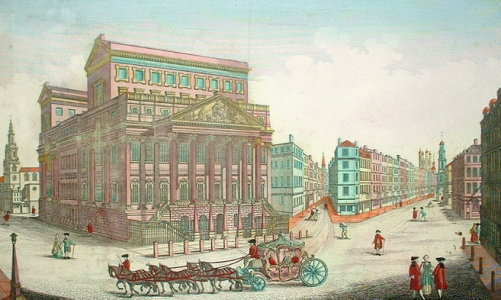

From medieval times foot races were common at village fairs and feast days. Runners would race to a local landmark and back or around a marked course, competing for a prize and some local renown. No efforts were made to time the races – accurate timepieces weren’t available – so comparing the ability of two runners who had never raced each other could only ever have been a matter of debate.

This began to change with the industrial revolution, when running was swept up in a growing obsession with time-keeping in all aspects of life. Factory owners demanded promptness and efficient use of time. Working lives were regulated by the clock, and running followed suit. In this atmosphere a new form of the sport emerged in which individuals competed alone, and against the clock.

This was the era of ‘pedestrianism’, when runners and speed walkers covered huge distances across the country or simply around a measured track within a specified time. The famous Captain Robert Barclay covered 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours in 1809 to win a huge bet. A few years later an elderly female pedestrian tramped 96 miles in 24 hours. Particularly impressive performances were reported in the newspapers, providing a target for other athletes to try to beat.

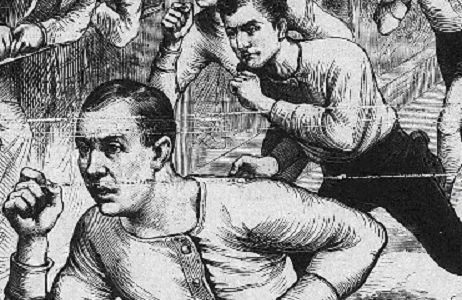

In the second half of the 19th century the obsession with times became even more intense. By universalising race distances, track surfaces and rules it was possible to compare different athlete’s times fairly and accurately. For the first time the keeping of national records became meaningful. The Amateur Athletic Association set itself up as their administrator, and ratified only those performances that had taken place under a strict set of conditions.

More haste less speed?

Naturally these developments emphasised the importance of quick times over everything else. Not everyone approved of this, particularly in Germany, where an alternative form of athletics had taken root. Here, athletics had developed into something more like gymnastics, where poise and form were as important as muscle power. In running events the winner was the competitor who could go as fast as possible whilst maintaining an effortless stride and graceful posture. To these athletes the straining sinews and grimaces of time-focused British runners were quite unbecoming.

But of course in the end it was the time focused version of running that conquered the world. And today, running’s obsession with measurement and record keeping has reached a new intensity, as GPS watches, heart rate monitors and social media comparison abound. For many people the measurability of running is what makes it such an engaging sport. But there is a growing movement for rejecting the clock and comparison, and focusing instead on pressure free running, technique and escaping the tyranny of the clock. Whichever form you choose, you’re in great historical company.